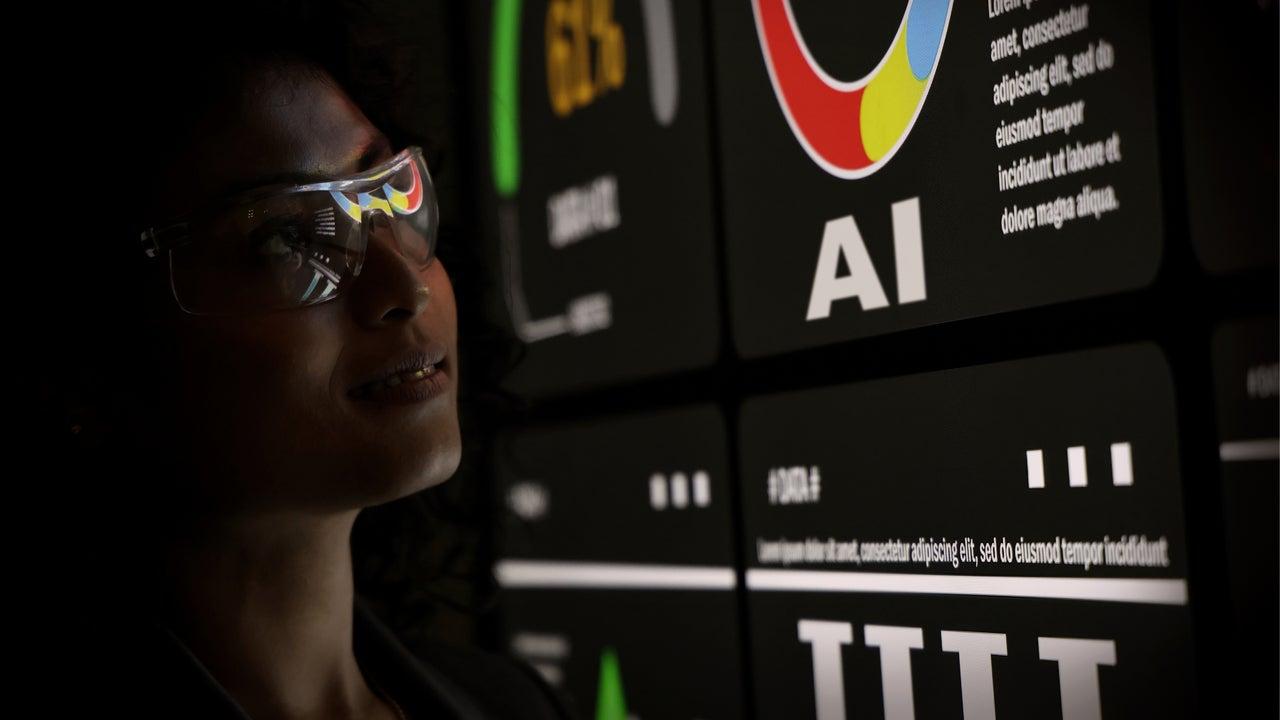

Genome sequencing will identify Helicobacter pylori resistance to important antibiotics and help choose the best treatment for each patient.

A team from the Institute of Biomedicine of Valencia (IBV), the Supreme Council for Scientific Research (CSIC), together with the National Reference Center for Campylobacters and Helicobacters (France), has developed a method supported by genomic sequencing that can predict with high accuracy the resistance of "Helicobacter pylori" to its main treatment.This tool allows choosing the most appropriate treatment for each patient.

More than half of the world's population is infected by this bacterium, which lives in the stomach and causes one of the most common chronic diseases in humans, although the majority of carriers do not show symptoms. When it appears, Helicobacter pylori causes gastritis, peptic ulcers, and, over time, increases the risk of stomach cancer and a rare type of lymphoma in the stomach.

Current treatments aim to eliminate the bacteria to avoid serious complications and combine different antibiotics with drugs that protect the gastric mucosa.“Treatments aimed at eliminating 'Helicobacter pylori' fail in almost 25 percent of cases, mainly due to the resistance of the bacteria to one of the antibiotics used,” explained Iñaki Comas, research professor at CSIC at the IBV, responsible for the study published in “The Lancet Microbe”.

Until recently, the standard way to evaluate the possible resistance of bacteria to certain drugs was bacterial culture.This method is based on the cultivation of bacteria under controlled conditions in order to obtain a sufficient population to study their behavior against drugs.In the case of H. pylori, this process is also useful, and the results are not always comparable between different companies.

Against this limitation, the author of the work has designed a method that replaces the culture and sequencing of the bacterial genome, with the aim of finding specific mutations associated with resistance to clarithromycin and levofloxacin, two reference antibiotics against "Helicobacter pylori".

"Although a positive culture (confirmation of the presence of bacteria in a sample) is necessary to obtain the genome of the bacterium, it is not necessary to do additional cultures to identify resistance, which saves time and resources. In addition, the method is more precise and reproducible, avoiding the errors associated with traditional tests," emphasized researcher Álvaro Chiner, from the Foundation for Sanitary and Biomedical Research of the Valencian Community.to study

With the resulting data, the team created a catalog of genetic mutations that allow identification of resistance in a single genomic analysis.Together, they revealed significant differences between different geographic regions and calculated the global distribution of these resistances.

The study specifies that in Southeast Asia up to 51.2% of the species examined showed resistance to clarithromycin, while resistance to levofloxacin was less than 13%.In contrast, in South Asia, more than half of the species were resistant to levofloxacin and less than 5% were resistant to clarithromycin.

a tool to promote surveillance and monitoring

According to the researchers, this approach is applicable on a global scale and can be integrated into genomic diagnostic platforms, adapting to the particularities of each region.“This technology can be used in clinical diagnosis to select the most appropriate treatment from the beginning,” Iñaki Comas emphasized.According to him, the gradual expansion of genetic sequencing in hospitals, especially stimulated after the Covid-19 pandemic, would facilitate the integration of this type of analysis for "Helicobacter pylori".

This is another, the way is considered the epidemiological disease of the antibiological disease and lead psychobacture pylorical plans.

This project is part of an international consortium financed and coordinated by Contanza Carmago from the National Cancer Institute. In addition to the Fisabio Foundation, several scientific research institutions from Spain, France, Japan and the United States are also involved. Its funding is supported by the European Research Council (ERC) and the Department of Science, Innovation and Universities. The laboratory of Inaki Comas at the IBV-CSIC is integrated into the CIBER for Epidemiology and Public Health of the Carlos III Health Institute and the Interdisciplinary Thematic Platform(PTI) CSIC Global Health.